Bass Connections Team Pursues First-ever Automated Fact-checking App

October 17, 2018

When it comes to real-time fact-checking, there’s (almost) an app for that

With an endless onslaught of news and opinion pounding us from traditional outlets, blogs and social media, fact-checking helps a weary public determine which political claims are accurate and which ones aren’t.

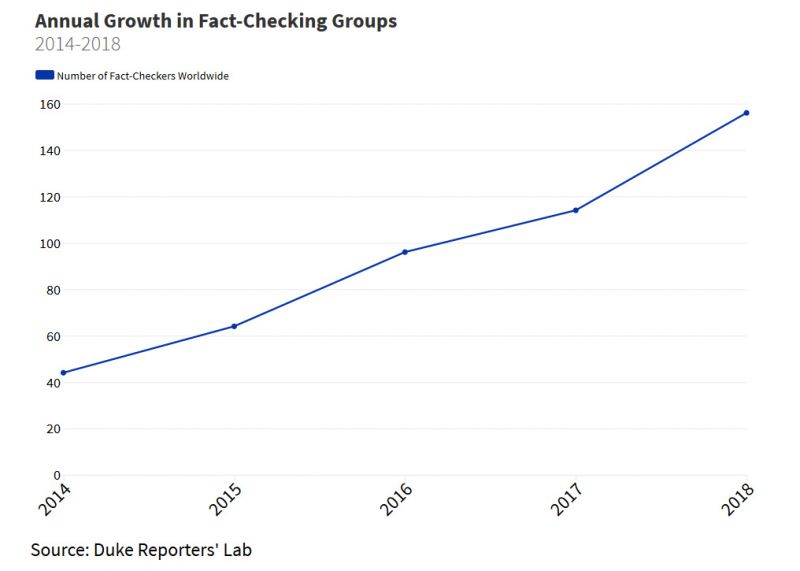

But there are now 156 fact-checking operations around the world, a number that has more than tripled in the past four years, according to the Duke Reporters’ Lab. And checking claims takes time.

So imagine this: You’re watching a State of the Union speech and the fact-checking pops up on the screen – in real time.

No waiting for the media to post stories on which statements were true, false or misleading.

No wading through the sludge to check the claims on your own.

The fact checks are right there on your smartphone, tablet or TV.

A Bass Connections project that combines journalism and computer science is working on such an app. Faculty who lead the project, which started this fall, say it would be the first to provide “pop-up” fact-checking in real time automatically.

The app doesn’t do the work of human fact-checkers – that’s still too complex for computers – but the goal is to match spoken claims with fact-check articles that have already been published, says Bill Adair, professor of the practice of journalism and public policy and director of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy who co-leads the Bass Connections project.

“It is about trying to take the journalism of political fact-checking and get it to the people when they need it,” says Adair, a veteran news reporter and creator of the Pulitzer Prize-winning website PolitiFact.

“Right now there’s a lot of good political fact-checking, but people have to go find it. They have to hear the claim, then look up the claim. What we’re trying to do is automate it so that the moment the claim is made by a politician, the fact check automatically pops up on their phone, TV screen or tablet.”

That’s much easier said than done, acknowledge Adair and co-project leader Jun Yang, a professor of computer science.

The apps being developed by Yang’s and Adair’s team rely on a database of fact-checks that were published by organizations such as The Washington Post, PolitiFact and FactCheck.org. The database grew out of an earlier partnership between the Reporters’ Lab and Google.

Right now there’s a lot of good political fact-checking, but people have to go find it. They have to hear the claim, then look up the claim. What we’re trying to do is automate it so that the moment the claim is made by a politician, the fact check automatically pops up on their phone, TV screen or tablet. –Bill Adair

The previously published fact-checks have value because politicians often repeat the same lines. So past fact-checks are relevant.

But a big challenge is matching the new statement to that fact-check because phrasing can vary and computers don’t understand all the nuances of spoken English. For example, take the sentences, “The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too wide” and “the animal didn’t cross the street because it was too tired.” Until recently, computers had a hard time determining whether “it” refers to the animal or the street. Besides resolving such ambiguities, computers also need to be able to detect paraphrases, and more generally, whether one statement logically entails another. These problems remain very difficult despite recent advances in AI.

“The accuracy bar is very high,” Yang says. “Pop-up fact-checking can give a true-or-false verdict, but if our matching algorithm makes any mistakes people are not going to be very happy about it.”

So, much like a Google search returns suggested answers or pages, the real-time app would return a “here is some helpful information” response related to the claim, unless the matching algorithm is absolutely sure about a true or false judgment, Adair says.

The team aims to have a proof of concept version done in the spring and would like to have more polished products complete in 2020.

The project continues work that began this summer during an intense precursor called Data+, a 10-week research experience for undergraduates that focuses on using “data-driven approaches to interdisciplinary challenges.”

Ethan Holland, a junior double-majoring in computer science and statistics, says the summer program helped him apply his classroom learning with a real-world problem -- truth in politics.

The first time we combined all the parts we had been separately developing into one system and could see real results was really exciting. –Ethan Holland ’20

“Knowing where to start was a pretty big challenge,” says the Rockville, Maryland, native. “We started with a very broad idea of what the final product should do, but very little idea of how best to go about getting there. Much of the process was trial and error. (Watch Holland’s presentation on the app project.)

“We realized after five weeks that we were building a model to answer too narrow of a question and had to go back to the drawing board. I'm not sure about our biggest success, but the first time we combined all the parts we had been separately developing into one system and could see real results was really exciting.”

Learn More

- Read more about this Bass Connections project, Data and Technology for Fact-checking, and a related Data+ summer project.

- Explore other politically-related projects: Making Young Voters; Gerrymandering and the Extent of Democracy in America; and How to Cure Political Polarization by Asking Questions.

- Read a related story by Steve Hartsoe, Bass Connections Marks 5 Years of Real-world Solutions.

By Steve Hartsoe; originally posted on Duke Today