Amplifying Stories of Environmental Racism, Resistance in North Carolina

October 10, 2022

By Sarah Grace Engel, M.T.S., Program Coordinator, Bass Connections

While stepping into a new era with the Duke Climate Commitment, Duke also looks back on a long state history of environmental justice advocacy and the injustices that necessitate it. Two Bass Connections teams are participating in this work of reflecting on the past and pressing toward the future of environmental justice.

Birthplace of a Movement

In September 1982, residents of Warren County, North Carolina protested against the state’s decision to build a toxic industrial waste dump in their community. At the time, Warren County was home to the highest proportion of Black residents out of all 100 counties in North Carolina.

Alongside civil rights leaders and environmental activists, members of this community took to the streets for weeks to prevent over 60,000 tons of contaminated soil from being dumped near their homes. The state built the dump anyway, and it immediately began to leak.

Nevertheless, the protests in Warren County shined a spotlight on the intersection between racial oppression and ecological harm. The protestors had ignited a movement that would forever change American environmentalism.

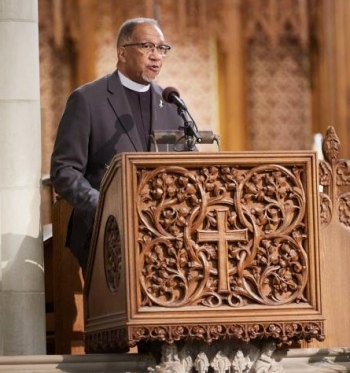

At the heart of the Warren County protests was Rev. Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., who had graduated magna cum laude from Duke Divinity School two years prior. He was among over 500 individuals arrested. Thus, it was not from a pulpit but from a jail cell that the reverend proclaimed a prophetic new term for what he’d seen in Warren County: environmental racism.

This year, two Bass Connections teams, Environmental Justice, Climate Change and Community Engagement and Collecting Oral Histories of Environmental Racism and Injustice, are building on 40 years of activism and research to further shed light on environmental racism and advocate for environmental justice in North Carolina and beyond.

Both will strive to walk alongside those who have lived their lives resisting environmental racism — long before the protests of Warren County, and long after.

As these two Bass Connections teams embark on a year of learning and research, they harbor cautious hopes of contributing to the longstanding struggle for environmental justice. One will focus on preserving the stories of those who have gone before, lest they be silenced, lost or ignored. The other will home in on one harmful set of practices that may, without intervention, become further embedded in the land and history of North Carolina.

Oppression Past and Present

Some hailed North Carolina’s 2021 House Bill 951, which set targets for carbon emission reduction, as a green energy milestone. However, Lee Miller, who is a lecturing fellow in the Law School and a co-leader of the Environmental Justice, Climate Change and Community Engagement team, calls it “the big legislative compromise.”

Why? For one thing, it is set to rely on swine waste biogas.

To those who live miles away from anything resembling a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), the repurposing of waste from the state’s millions of hogs might seem clever and efficient. For the residents of eastern North Carolina communities studded with pig farms, however, the use of swine waste for energy will further entrench toxic forms of industrial agriculture that have been harming people of color for generations.

“This problem is actually a 500-year history of problems,” explained Jon Choi, co-manager of the project, starting with European colonization of Native lands and stretching through slavery and Jim Crow to their legacies today.

Miller agreed. “It's very easy to draw a map that shows: here is the concentration of enslaved people in North Carolina in 1860; and here's where swine farms were built in the 1980s and early 1990s with no controls on air pollution whatsoever and completely inadequate control of water pollution.”

Stopping to Smell the Swine Waste

Before diving into policy research surrounding CAFOs, Miller wanted students to have a visceral understanding of the harm done by these agricultural systems and the pollution they create. To this end, one of the team’s first group activities was visiting hog farms and waste lagoons in eastern North Carolina. It did the trick.

Touring CAFOs and speaking with community members, the team heard stories of polluted air, undrinkable water and poisoned community relationships. A pastor told of church steeples stained by waste spraying and children’s health endangered by nitrates in the water. A contract farmer spoke of their economic situation as a form of servitude.

Project co-manager Renata Poulton Kamakura, who is currently earning their Ph.D. in ecology, described the powerful impact of this brief trip. When driving east, Kamakura explained, their surroundings seemed relatively benign. Driving back after two days immersed in the stench of swine waste, Kamakura’s view was different. They spotted an abundance of damaging agricultural practices, from CAFOs to waste sprayers.

Such an experience can have a way of “changing how your brain processes what’s in front of you," Kamakura said.

Choi agreed that the trip was transformative. A Duke Law School graduate and current marine science and conservation Ph.D. student, he had learned about these issues before, he said, but “it’s an entirely different ballgame to hear people tell their story.”

Stories of the South

The need to record such stories of oppression and of resistance is the driving force behind another Bass Connections team: Collecting Oral Histories of Environmental Racism and Injustice. Project manager Cameron Oglesby explained that despite increasing awareness of environmental injustice, little has been done to preserve the wisdom of those who have experienced it.

“We have elders who have been in the trenches, who have been on the frontlines, who are starting to get older, and whose stories may be lost,” Oglesby said. “We wanted to make sure we were collecting and preserving those experiences so that they can live on and we’re not losing that entire chunk of history.”

As the issue of swine pollution shows, the history of environmental injustice is still being written. Oglesby, who is influenced by her own experience reporting on environmental racism in swine farm practices, and the other team leaders have encouraged participants to draw on their geographical, family and ancestral backgrounds in their storytelling, and some are reflecting on oppressive systems they have seen or experienced themselves.

For example, assistant project coordinator Ameena Hester’s family is rooted in the Outer and Inner Banks regions of North Carolina, which have seen rapid gentrification and development without the adaptations of climate-resilient infrastructure. Her first introduction to the term “environmental injustice” was transformative, she said, as it “put into words a lot of lived experiences of mine … It was that sort of opening of doors that vocabulary can do for someone.”

Frameworks for Participation

Now, the team seeks to create space for the words and stories of those who have experienced environmental racism and amplify historically marginalized voices through archival websites, podcasts, short-form documentaries and more. They are also being thoughtful about the history and ethics of community-engaged research, which has often been tainted by extractive research practices.

To help them prepare, students in a linked Summer 2022 Story+ project spent six weeks focused on creating a philosophical framework of research ethics. The results of this project undergird the work of the yearlong team, which centers genuine partnership and informed consent.

According to Oglesby, this intentional approach to oral history collection guides the team’s efforts “with the hope that the project becomes more than just a repository for oral histories,” but rather an open resource for communities to advance the work of environmental justice activism. Hester explained that, with “sovereignty” over the data collected, these communities will continue to own their stories even after outside researchers have documented them and moved on.

As part of their learning and preparation, team members attended the 40th anniversary march for environmental justice in Warren County. As they spoke with community members who had worked toward healing for decades, the students felt a deep sense of resilience and celebration.

Oglesby explained the complexity of the work ahead: “Environmental justice is not just about pollution or harms. Environmental justice is about empowerment, it’s about place-based joy, it is a fight for culture and spirit as much as it is a fight for health.”

To tell this story well, Oglesby said, the team must portray “all that these communities are: not victims but legends.”

Learn More

- Learn more about the Collecting Oral Histories of Environmental Racism and Injustice and Environmental Justice, Climate Change and Community Engagement teams.

- Submit a proposal for a 2023-2024 Bass Connections project by November 7.

- Explore more projects in the Energy & Environment and Race & Society themes.