Christine Crute

We had to redesign our research plan overnight and determine how to get usable data. On a daily basis, I learned to handle unforeseen issues that arose and determine new routes of study.

Degree

Ph.D., Integrated Program in Environmental Health and Toxicology (ITEHP) ’24Project Team

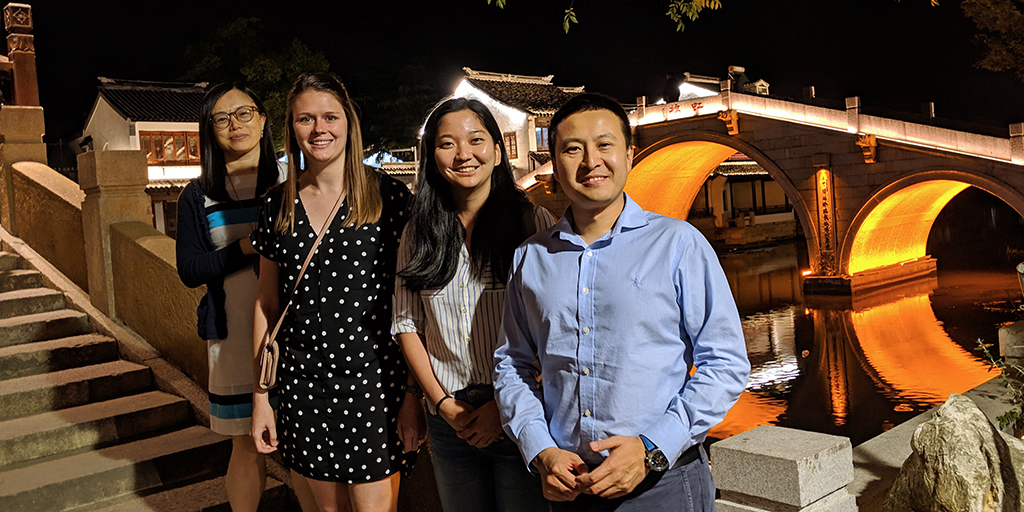

In May 2019, I arrived in China with my research team and a detailed plan to study the health effects of maternal electronic-waste exposure on child development. To accomplish this, I planned three phases of work, the first of which was to conduct fieldwork in Taizhou, China, with a Duke faculty member and two master’s students. However, my detailed plans were turned upside down from our very first day in the field. This is a story of how a group of novice field researchers approached their first fieldwork experience, highlighting a few of the lessons that we learned.

This project started years ago, when Liping Feng, Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, became interested in a population of people in Guiyu, China, who were involved with an intensive process of electronic recycling. Also known as e-waste, electronic waste is, more or less, exactly as it sounds. When we consumers upgrade our smartphones, computers and televisions, the old items are discarded. With increasing state regulations against dumping electronics in landfills, and the knowledge that electronics contain precious metals like gold and copper, recycling is an enticing option to many of the parties involved.

Along with much of our landfill-destined waste, e-waste is often shipped from the United States to developing nations under government approval or illegal transfer. Developing countries can be paid to take our waste, or they may pay for things like e-waste that they can recycle and sell to industries. Either way, our e-waste ends up in countries like China, where communities take it in, disassemble it, harvest the reusable materials and make a small profit.

This is what happened in Guiyu, the largest e-waste site in the world. Due to the processes of e-waste recycling, the entire community is highly polluted. Lead, chromium and other heavy metals contaminate the drinking water, and the air is filled with dioxins, flame retardants and other chemicals. Just Google “Guiyu” for a flood of images of severe environmental pollution and hazardous health conditions.

Since Guiyu has become the poster child for harmful e-waste recycling and environmental devastation, the community is largely inaccessible to foreigners and scientists alike. So, Liping turned to Taizhou, a region south of Shanghai said to be the second largest e-waste recycling town in China. Liping and her collaborators from Shanghai collected umbilical cord blood samples from a local Taizhou hospital last summer, which gave us a reference of possible chemical exposures during pregnancy.

For this trip, our fieldwork goals were to conduct community surveys and collect exposure data from people living in the e-waste community. Community surveys are especially useful in fieldwork because you can collect a breadth of information about a research topic that you may not find in the published literature. Our survey investigated public perception of e-waste in the community. For instance, we sought to learn how many community members were familiar with this process, how they viewed the benefits and drawbacks of e-waste recycling and what health effects they observed.

Next, we planned to recruit a cohort of people to wear silicone wristbands that collect the chemicals we are exposed to during our daily lives. Analytical chemists can then process the wristbands and determine the amount and type of chemicals the wearers were exposed to in their community.

Soon after beginning the field research, we quickly found out that this study would not go as planned, for a long list of reasons. However, our team learned invaluable lessons while navigating the challenges and gathered valuable information for future studies.

Lesson 1: Learn to plan on the fly.

As an organized, detail-driven lab scientist, I’ll admit that this was the most difficult lesson to learn. However, I received a lot of practice making quick decisions and changes to the study design because the entire e-waste community industry had been restructured less than a year before we arrived.

Traditionally, e-waste was recycled in small “mom and pop” shops. However, with new government regulations, the e-waste industry had been moved to a large industrial park. Many locals lost their jobs as the industry brought in migrant workers to live in company-run dorms. Considering the high security and inaccessibility, we were unable to interact with current e-waste workers as we had originally planned.

We had to redesign our research plan overnight and determine how to get usable data. On a daily basis, I learned to handle unforeseen issues that arose and determine new routes of study.

Lesson 2: Design field research in partnership with local community members.

Our Shanghai collaborator was knowledgeable about environmental pollution in the area and had contacts at the local hospital. However, we did not have any contacts in the community itself, which made correspondence with locals difficult.

Our Mandarin-speaking students had trouble understanding some of the local dialect, so we learned the importance of recruiting students or health officials from the local community to help us conduct interviews. Furthermore, some citizens were concerned about our motives and government repercussions, so we redesigned our recruitment plan to work with a trusted doctor that had established relationships within the community.

Lesson 3: Prepare for crisis (and stay calm).

As mentioned above, we would likely have had more community engagement with the support of trusted locals. Additionally, that partnership could have alleviated people’s concern over seeing foreigner scientists collecting materials, especially during this time of political tension between China and the United States. After the Taizhou police were called to investigate our purpose, I took a trip to the police station with one of my students. Thankfully, the Duke Global Health Institute prepared us for emergencies, and I had the necessary contacts to speak on the phone with the officers and verify our identity and purpose.

Lesson 4: Embrace the local culture.

Research goals and experimental planning is greatly improved with knowledge of local culture. Anticipation of people’s concerns, fears, values and desires helps researchers to design the most effective studies that can do the most good in the community.

Even more so, the more you learn about people with seemingly different cultures, the more you see our human similarities. So my best advice is to eat the strange food, learn about foreign holidays, religions and government, ask questions about daily life. If you’re lucky, you will discover a delicious new cuisine or expand your ideas and opinions.

Global health work is certainly not without challenges. But for the sake of science and humanity, this field perseveres with research toward improving health of populations across the world.

And so, despite the challenges this summer, my love for this research assures me that this novice isn’t giving up on the field yet.