Research on the ReMo

Originally published in the Spring 2016 issue of GIST by the Duke Social Science Research Institute (SSRI)

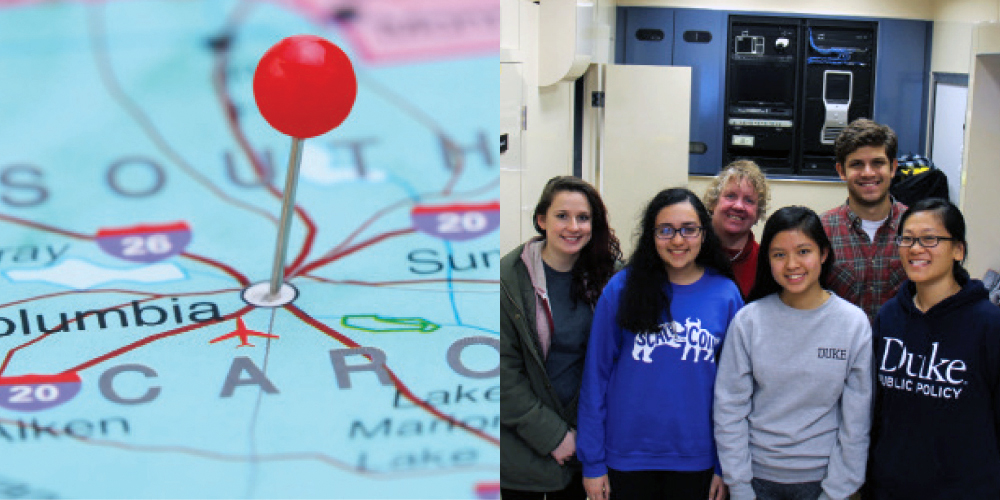

Less than three months after devastating floods washed over parts of South Carolina, Duke’s ResearchMobile trundled down to Columbia, one of the hardest-hit areas, and set up shop in the parking lot of a shuttered Piggly Wiggly. Eight Duke students and two faculty spent part of their winter break to sit down with locals in a cubicle in the upfitted RV and say, “Tell us about what happened and how it affected you.”

What those field interviews yielded could be turned into policy decisions and steps to reduce the risk of such events and minimize their effects on the community as a whole. The quality of the information the researchers learned by being at the site of the disaster, and from talking with people face-to-face, was much greater than if the team had stayed on campus and sent out questionnaires.

The project became part of Bass Connections, which paid for the lab’s travel expenses and now enables the student researchers to analyze their data over the spring semester.

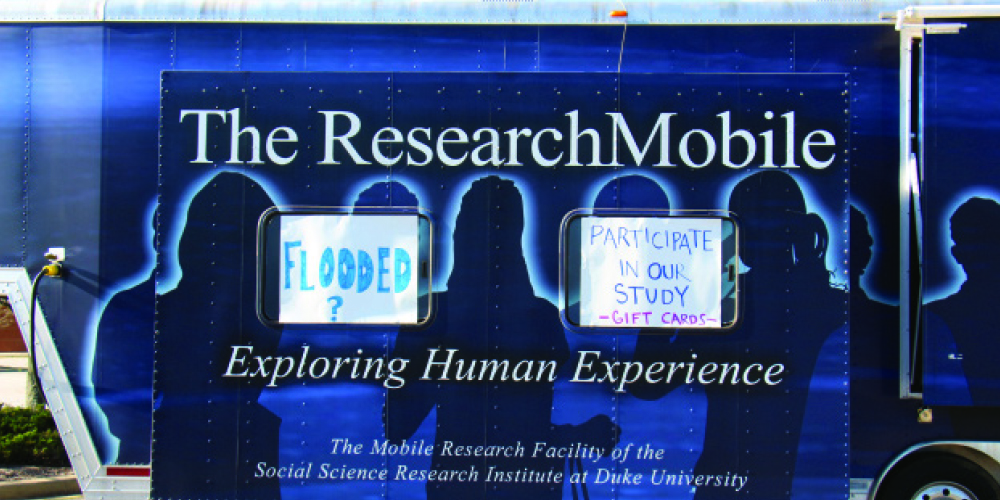

Duke’s Social Science Research Institute acquired the mobile research lab, which the team that took it to South Carolina dubbed the “ReMo,” about six years ago through funds from the National Science Foundation. The research trip in December and January marked its first voyage across state lines. Picture an RV stocked with portable equipment useful to researchers—video cameras, heart-rate monitors, soundproof cubicles and a coloring table to entertain children brought by interview participants.

Alexandra Cooper, SSRI’s associate director for education, admits that before she went on the flood research trip, she was skeptical about the need for such a fancy rig. Just set up a table and umbrella and sit and talk with people, she thought. But almost as soon as she arrived in South Carolina, she became a convert.

First, there was the unseasonably cold weather. People are less inclined to sit outside and take a survey if their fingers are numb.

“Having a heated ResearchMobile is nice,” Cooper said. And the sheer size of the vehicle adds legitimacy to the research. “It sends a clear message to the community that we care about the topic. We’ve devoted effort to getting down here. It says: If you think our research topic is something we should find out about, come talk to us.”

The novelty of ReMo helped recruit subjects, too, said Connie Ma, a graduate student in public policy who spent the week after New Year’s interviewing flood victims in the mobile lab. A few days after ReMo arrived, a local news station sent out a TV crew to see what was going on.

“We never would have gotten that kind of coverage if we had been located in a building on the USC campus,” she said.

As word spread among community members of the Duke team wanting to talk about flood experiences, more and more people ventured in. Anya Bali, a freshman at Duke interested in the social sciences who is from South Carolina, signed on to the project to acquire some hands-on experience in collecting qualitative data.

“The flood was personal for me,” she said. “I wanted to learn how people were responding to the floods, outside of the context of what my friends told me.”

Bali was surprised that more than a hundred people braved the cold to talk about how the disaster affected them.

“I didn’t think people would want to talk about their personal experience and the losses they faced,” she said. “But they were all very eager to share their stories.”

The response from the public surprised even experienced researcher Elizabeth Albright, assistant professor of the practice of environmental science and policy methods at the Nicholas School of the Environment, who was principal investigator of the project.

“Many of the participants lost nearly everything they owned in the flood,” she said, “yet they wanted to talk with us, they wanted their story to be told.”

Some, still working through FEMA claims and unable to return to their homes, felt forgotten after the floods moved out of the crisis news cycle.

Cooper added, “A lot of people commented that we were the first group to ask them what it had been like, what happened to you, in a way that wasn’t about collecting numbers, about property damage.”

The research uncovered surprising gaps, such as the extent to which government-organized assistance is centered on insurance.

“Insurance helps people who already had something,” Cooper said. “But if you don’t have things that have much market value before the flood, insurance won’t help after the flood in replacing what you lost.”

Because of the way the flood unfolded—a breach of a dam maintained by a homeowners association causing another dam to breach farther downstream—people who weren’t normally in areas prone to flooding were unexpectedly in the path of a flood. This pointed to deeper policy issues of how to ensure that a dam maintained by an HOA is adequate for the risk of flooding.

The researchers heard from people with nearly identical homes harmed in the same way who had gotten very different advice from different contractors on how to repair the damage. Cooper said that residents told her few local contractors had extensive experience with flood damage. “Residents didn’t have any good way to assess who knew what they were talking about.”

Even residents who did not lose their homes still suffered from the flood. Schools were closed for a week, and then had delayed openings for weeks after that. Parents who had to go to work suddenly had to find and likely pay for temporary childcare. While some businesses were working around the clock—such as a store that rented generators—other businesses, like restaurants, were closed. Their employees then didn’t get paid, and families who relied on those paychecks had to scramble.

“We got a sense of the many different impacts an event like this can have across a wide range of socioeconomic groups,” Cooper said.

The student researchers learned firsthand the complexities across all stages of field research. First, the logistics—finding a visible spot for the ReMo and obtaining permission to park there for a week; acquiring a wireless hotspot so participants could complete the survey on an iPad; rigging up a clear shower curtain liner as a windbreaker over the doorway, because shutting ReMo’s door might discourage walk-in participants. Then, recruiting participants, which initially meant stapling fliers to telephone poles. Finally, the questionnaire itself: Each student got to include a question pertinent to his or her research, and crafting the language was challenging.

“We had things like, ‘flood-plain zoning,’” Ma said. “People weren’t sure what that meant, let alone have an opinion on whether the city should do a better job of it.”

Now in the data-analysis phase, the students are learning NVivo, a software program valuable for many social science researchers, and cleaning and recoding the data. Albright plans to follow up with study participants at six months and a year.

“Extreme flood events have occurred across several regions,” she said, “and it is important that we learn from these events.”

Any Duke researcher interested in using the ResearchMobile should contact SSRI.

“It’s a great tool,” Cooper said, “but not if it’s parked at Duke and not in use.”

Learn More

- Read more about this project team, Individual and Household Responses to the October 2015 Floods in South Carolina.

- Explore Bass Connections in Education & Human Development.

- Find out how to get involved in Bass Connections.

Photos courtesy of Connie Ma: The ReMo on site in Columbia, SC; The research team (left to right): Libby Dotson, Anya Bali, Betsy Albright, Clara Wang, Alican Arcasoy, Connie Ma (Not pictured: Alexandra Cooper, Maya Durvasula, Christopher Molthrop, and Noah Triplett); A reporter from Columbia’s WLTX interviews Anya Bali, Duke freshman and South Carolina native; Canal breach in downtown Columbia, as seen from Coble Plaza at Riverfront Park; Posters taped to the ReMo attracted curious Columbia residents and potential survey participants.