Bass Connections Team Starts Conversation on How Durham’s History Influences the Health of Its Residents

November 27, 2019

Dr. Jeff Baker wanted to get Duke Health caregivers talking about how their patients’ medical issues aren’t always matters of personal choice but can come out of historical social determinants that are challenging to change.

That’s an important task, but the 12 undergraduate and two graduate students in his Bass Connections project had an additional mission in mind.

“What was remarkable was the students brought different emphasis,” said Baker, a professor of pediatrics and co-director of the project with historian Robert Korsted on the history of health care disparities in Durham.

“The students stressed the importance of listening to people in community who were also advocating for themselves: Not just seeing these people as being victims of historical forces, but as people how spoke up for themselves. We took on a very large historical project, but throughout it, the students made sure the focus was on the people and their stories.”

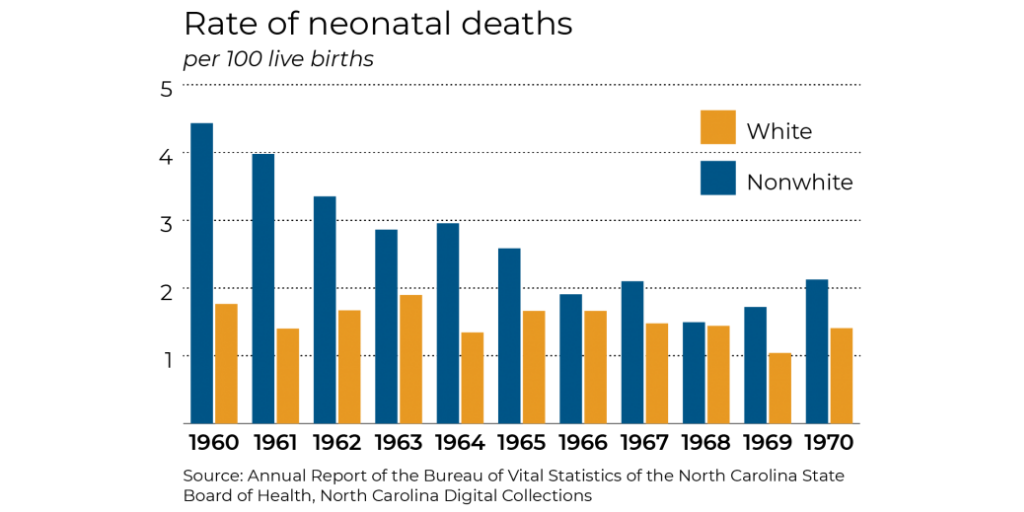

The result was a review of health care disparities through four crucial periods of Durham’s history: tuberculosis in the early 20th century; childbirth during the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s; AIDS in the 1980s; and obesity and diabetes in contemporary Durham.

In collecting data and stories, the students showed how race and other social determinants – social class, sexual orientation and housing – influenced medical disparities.

Baker is getting the conversation he wanted. Duke and Durham community leaders are listening to what the students found. An exhibit based on the project findings has been on display at sites in Durham, including the Durham County Department of Public Health. It is currently on display at the Medical Center Library in the Seeley Mudd Building. They also produced audio interviews of local residents and a short video documentary on AIDS in Durham in the 1980s, which are part of the exhibit.

Below, Baker and two of the students, Dan Crair and Meghana Iragavarapu, talked about their findings and the people behind the stories they uncovered.

Q: Why is a historical approach valuable in understanding contemporary health care in Durham?

BAKER: History is about understanding what determines the determinants. It’s easy to show diabetes rates vary enormously in different neighborhoods, but the question then becomes: Why are they lower in West Durham and Old Durham than in East Durham. One answer is there are more grocery stores in West Durham, and people have access to healthier food. But why is that?

What we show is that some ways East and West Durham started out similarly, but then they go in different directions. West Durham was a predominantly white mill village, and the people there got the loans they needed to buy their houses. East Durham is primarily African American, and because of redlining, they were unable to buy their houses.

When the mills started closing and the economy changed, West Durham residents had the equity to stabilize the neighborhood, attracting investments including grocery stores. In East Durham, however, the houses are sold to landlords, who jacked up rents, ignored maintenance. This led to a pattern of disinvestment. It became a food desert. In these kinds of ways, historical structural patterns became a factor in health issues.

Q: You got to interview a number of people for this project. What are some of the stories that you’ll take away with you?

IRAGAVARAPU: I met a community health worker in East Durham who told me about one of her patients. The neighbors were always calling 911 for her because she would come to their homes needing help. Ambulances would come, but she would refuse to get in.

I didn’t understand this behavior, so I asked the health worker why someone would refuse treatment in an emergency condition. She said for one, the woman was scared of medical bills, which for a lot of people in this community is a concern. Two, she didn’t trust the treatment of the doctors she sees. She’s black and for many years she’s seen hospital doctors, but she never felt they understood her or develop a relationship. It’s a legacy of systematic racism. The doctors don’t listen to her and don’t relate to her condition, so she refuses to see them, even though it means her health suffers.

The story made me sad, but what really concerned me is the story didn’t seem isolated. It’s something that happens across Durham. I’m a pre-med student, and I hope that in my doctor’s office, people would feel comfortable to discuss all their issues; they would see it as a safe space. But because of the history, that’s not there.

BAKER: One of the things that I learned studying childbirth during the Civil Rights Era is that African Americans suddenly had access to better health technology after desegregation. That’s a good thing. But the other thing that happened is they lost Lincoln Hospital, which for generations served the black community in Durham. The hospital was very trusted in that community, and that’s essential in health care.

Q. How did this project provide you opportunities to expand your Duke education?

CRAIR: For this project I studied the AIDS crisis in the 80s. Previously, I was with DukeEngage at WISER working with secondary school students in rural Kenya who educate their peers on sexual health education, reproductive health and how to avoid HIV. This project was a way for me to look at this issue from an entirely different angle. So I’ve been able to work with Kenyan students who are trying to lower HIV rates. I’ve been able to look at Durham to see what were the obstacles to people getting access to treatment. And I hope now I’ll be able to work in a lab to explore ways to continue to improve care for people with HIV. The combination of these experiences will help me understand the different roles a doctor plays in health care.

BAKER: One reason why we wanted to run this as a Bass Connections project was that you get to work with all these great students. It was an attractive project for undergraduates looking for real-world experience interviewing human beings and engaging in work that tells an important story.

Where to See the Exhibit

The students’ findings are presented in posters currently on exhibit on the second and third floors of the Medical Center library in the Seeley Mudd Building.

This exhibition is cosponsored by the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities & History of Medicine and the Medical Center Library & Archives. It is made possible by a Duke Bass Connections grant.

By Geoffrey Mock; originally posted on Duke Today

Learn More

- Read about this project team, Documenting Durham’s Health History: Understanding the Roots of Health Disparities.

- Check out a reflection by Meghana Sai Iragavarapu and browse other stories from students.

- Mark your calendar for the Bass Connections Fair on January 24.